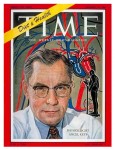

Ancel Keys on the cover of Time

Yesterday’s publication in The New England Journal of Medicine about primary prevention of heart disease from the Mediterranean Diet brought me back to an afternoon 20 years ago, when I walked up the hilly road from the town of Pioppi, Italy, to interview Ancel Keys and his wife Margaret, and stayed for dinner. Margaret herself is an unsung heroine in the annals of public health — she was with Ancel every step of the way, recording diet logs in homes in Crete, taking blood samples to measure blood cholesterol on the crude paper methods available in the ’50s and ’60s. But that’s another story.

Ancel Keys discovered, you might even say invented, the Mediterranean Diet. He had already done pioneering work studying the effects of starvation on Quaker volunteers in World War II, and he also invented K-rations (chocolates, sausage, and cigarettes, but enough to survive behind enemy lines) — the K was for Keys. Then in the ’50s, after the war, living in cold poor London, a cardiologist in Naples invited him to visit the land where there was almost no heart disease. There was some — mostly among the rich and northern Europeans who went to the rich hospital. But in the hospital for the poor, there was almost no coronary artery disease. Keys, intrigued, and attracted to the warmth of southern Italy, went down to explore. When he later spoke to cardiologists about his hypothesis that diet played a role in the development of coronary artery disease, the reception was as cold as a London winter in an unheated flat.

These days, Keys is known, and often pilloried, for his hypothesis that dietary fat, especially saturated fat, can raise blood cholesterol and increase the risk of coronary heart disease. He dismissed Yudkin’s theory that sugar played a role, too. We can debate those issues, and the sciences of nutrition and cardiology have certainly advanced since the 7 Countries study was published…and changed everything.

But the discovery of the health benefits of the Mediterranean Diet transcends those quibbles. Long before Michael Pollan wrote about the trap of “nutritionism,” Keys pointed to the power of dietary patterns. It’s the whole that matters. In The New York Times story about the NEJM study, one of the researchers called the Mediterranean diet a “black box.” That is, we don’t know exactly what foods or ingredients or nutrients or phytochemicals are most responsible for its extraordinary healthfulness. We just know that the closer you get to the dietary pattern, the less likely you are to develop heart disease, diabetes, and probably dementia, and the longer you are likely to live. The requirement to study a whole dietary pattern, rooted in agriculture and human culture and history and lives lived, is a challenge to modern science and medicine, with its reductive bias. The truth is, we don’t know as much as nutrition as we think we do. We have a lot to learn from the ways that successful human societies developed their frugal, sustainable, delicious cuisines. That includes the China diet, and many others. Keys, certainly a classic reductive data-based scientist in many ways, was instrumental in leading us in this nourishing, soulful direction.

The chapter I wrote about meeting Ancel Keys in my 1997 book Tonics is here.

I’m so pleased that my first post on my new site is about my first story for Zester Daily. I’ve been a big fan Mary Taylor Simeti’s books, such as On Persephone’s Island, and Pomp and Sustenance, since the ’80s. But I met Mary herself just this September, on a wonderful press trip organized by Oldways on the Sicilian island of Pantelleria. (Here’s a picture, courtesy of Oldways, of Mary flanked by Ihsan Gurdal of Formaggio Kitchen on the left, and Rolando Beramendi of Manicaretti food importers on the right.) One day, sitting together in the back of the van, between pointing out caper bushes and pomegranate trees (I had never seen either), she mentioned that her Nero d’Avalo wine was finally going to be available in the U.S. soon. It had taken a long time for the FDA to approve the label, possibly because it had an anti-mafia seal, she told me. To say I was intrigued is an understatement. Read my story here, and then do yourself a favor and look up some of Mary’s books. I’m quite enjoying re-reading On Persephone’s Island myself.

I’m so pleased that my first post on my new site is about my first story for Zester Daily. I’ve been a big fan Mary Taylor Simeti’s books, such as On Persephone’s Island, and Pomp and Sustenance, since the ’80s. But I met Mary herself just this September, on a wonderful press trip organized by Oldways on the Sicilian island of Pantelleria. (Here’s a picture, courtesy of Oldways, of Mary flanked by Ihsan Gurdal of Formaggio Kitchen on the left, and Rolando Beramendi of Manicaretti food importers on the right.) One day, sitting together in the back of the van, between pointing out caper bushes and pomegranate trees (I had never seen either), she mentioned that her Nero d’Avalo wine was finally going to be available in the U.S. soon. It had taken a long time for the FDA to approve the label, possibly because it had an anti-mafia seal, she told me. To say I was intrigued is an understatement. Read my story here, and then do yourself a favor and look up some of Mary’s books. I’m quite enjoying re-reading On Persephone’s Island myself.